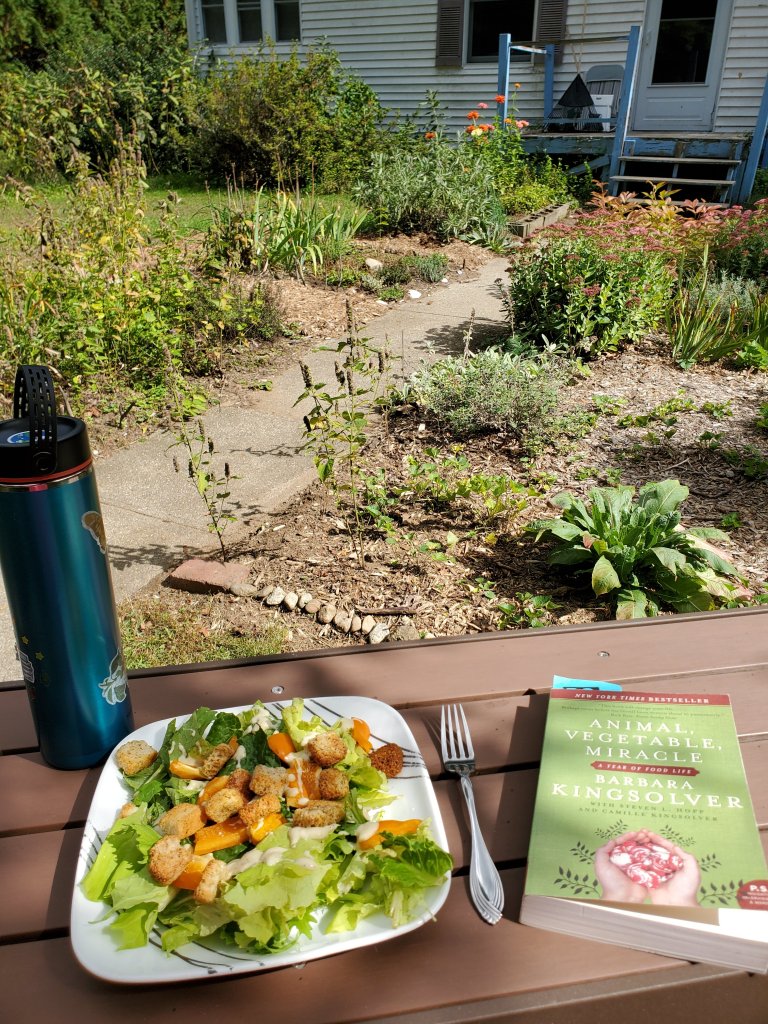

I recently finished re-reading Animal, Vegetable, Miracle by Barbara Kingsolver after 10 or 15 years, and man, was it a wild ride.

The book is a series of linked essays, with some chapter-end pieces added by Kingsolver’s college-aged daughter who loves to cook. It documents their family’s Year of Local Eating experiment, which they undertook while living on a farm property in rural Virginia. It’s a beautiful piece of writing, by turns wry and funny, reflective and fierce, that looks deeply into the growth of local food culture and heartily champions this way of eating (and living).

When I first read this book, I was all fired up about it. What a way to live! What a way to get more sustainable, be kind to the environment, nourish ourselves, build a culture around food, and live a healthy lifestyle! It went completely under my radar, back then, how this is basically the eco-friendly dream of the educated, white, liberal, abled, middle to upper middle class. A soothing fantasy about doing good in the world with the power of your mighty grocery budget. On top of which, with all of its moralizing about good local foods and evil processed foods… it’s also a solid part of diet culture.

“Detoxing, clean eating, and a fixation on whole foods have replaced the calorie-counting, low-fat-yogurt dieting of the 1980s and 1990s. But they are just as much about restriction and rules as anything Jenny Craig ever told you to do.”

–Virginia Sole-Smith, The Eating Instinct: Food Culture, Body Image, and Guilt in America

Eco-food, clean eating, eco-gastronomy, alternative-food, locavore, a whole foods diet, natural and organic food. Whatever you’re calling it, this is a set of food rules. It paints some foods as virtuous, healthy, safe, and nutritious, and others as bad, unhealthy, dangerous, and poor in nutrients. I’m not saying that there is no science behind these claims, or that it isn’t a great thing to buy from local farms if you have the access and affluence to do so, or to cook with whole food if you have the time and ability to do that. This style of eating does some great things, like keeping money in the local economy, and preserving small farms (and thus the type of landscapes we suburbanites feel good frequenting). It also helps to build local food resilience for the next time supply chains get disrupted, and it can be a healthy way to nourish oneself (though by far not the only legitimate way). But my lord, the American cultural landscape did not need one more thing for us to feel guilty about around food. And that is the engine that drives this book. (And similar books, like Michael Pollan’s The Omnivore’s Dilemma.)

I felt like Kingsolver was out of touch in this book about class. She insists that buying local foods can be as cheap as processed and imported foods right alongside explaining the subsidies and agribusiness practices that make those lower prices impossible. She suggests, also, that it’s a question of investing money now (or labor, if you have access to land, time, and physical ability, and are growing some of your own), to save healthcare costs and environmental costs later. Well, sure. But that’s a short-sighted recommendation for people who legitimately struggle to make ends meet. It’s like telling them their grocery woes would be over if they just bought in bulk at Costco. Not everyone has the up-front capital to invest.

The picture she paints of a happy family that grows, cooks, and eats together, spending hours per day in each other’s company engaged in that project reads to me as the eco-friendly version of the conservative longing for the simpler times of the 1950s. Only this time, she’s reaching back (and out) to draw lessons from Italian culture (on her Italian vacation interlude), and to some Amish friends (as she visits them during a summer family road trip). But don’t be concerned—her display of vacation affluence is surely mitigated by her admission that back when she was getting started in her career, she, too, was stuck eating rice and beans, or maybe cup o noodles. And don’t forget her Southern farm kid background! She understands poverty.

As with SO MUCH of the environmental gospel, this book makes absolutely no mention of gardening or cooking while disabled. Given what I’ve been doing with my life since the last time I read it, that felt incredibly marginalizing and pretty tone-deaf. I freaking love local food. I have a CSA share every year, and I love to cook. I also rely constantly on processed convenience foods to support my cooking, because the amount of physical ability I have to invest is limited. My cooking style will always be semi-homemade at best. Kingsolver’s food moralism would like me to please feel bad about my grocery-store jars of tomato sauce and the pre-chopped refrigerated jarred garlic, never mind the graham crackers and cheez-its in the cupboard. Don’t get me started about her vision of parenting around food and cooking that begins with the fundamental premise that your kids will want to participate.

And it’s not just physical impediments that can make cooking with whole foods hard. Scratch cooking takes a ton of forward planning, and remembering what you have on hand, and what you can do with it. Sometimes, depending on the recipe, it takes careful focus or multitasking abilities. Anyone who struggles with executive dysfunction thanks to neurodivergence or depression is going to have a mighty tough time with some portions of that (which portions vary by individual). I guess that whole segment of the population is doomed to lesser quality food? She doesn’t raise the question, much less suggest an inclusive answer.

So I have a mighty hard time swallowing the “this is the ideal diet/lifestyle for everyone” thread that runs through the book on this read-through. Despite Kingsolver’s beautiful and impassioned writing, I can’t help but see her as another unwitting emissary of diet culture, classism, and ableism. It’s not what she meant to do, but it’s where her socio-economic position and life experience led her. I respect how hard she was willing to work to live her values for a year and communicate them with all of us. That takes guts and dedication. Yet I simultaneously appreciate that my life experiences since my first encounter with this book have allowed me to see where it goes wrong, as well as where it goes right.

May we always learn better, and do better. (This author included.)